|

Introduction to the Epistle to the Hebrews This is a series of studies that explore the meaning of the Epistle to the Hebrews. ©2001 by James A. Fowler. All rights reserved. You are free to download

these outlines provided they remain intact without alteration.

An Introduction to the Epistle to the Hebrews

The epistle to the Hebrews has suffered from anonymity. There is anonymity of both author and recipients because these details are not included in the text of the letter. Such anonymity makes the document suspect in the minds of some for it provides no specificity of its intended meaning within a given context. The anonymity of writer and reader allows the epistle to be abstracted and generalized without a specific sitz em leben (setting in life) to provide historical context and a basis for specific amplification and application of the meaning of the words. Anonymous text allows for a dilution of meaning in interpretation of the text, or allows an expositor to run rampant with personal presuppositions which are imposed upon or applied to the text. In other words, anonymity can diminish exegesis (interpretive meaning drawn out of the text) and/or facilitate eisegesis (interpretive meaning read into the text). In either case, whether subtractive or additive, such interpretation cannot and does not take into account the full intent of the original author to his recipients, and thus diminishes the value and meaning of the text for subsequent generations of readers. This has certainly been the case in the interpretation of the epistle to the Hebrews. The letter has suffered from neglect and misuse. The regrettable consequence of the anonymous authorship of this literature has been the reluctance of some Christians to accept it as fully authentic and authoritative. Even in the early church it was little used and cited. Hebrews has suffered from a subtle skepticism throughout Christian history because of its unknown authorship, and contemporary interpretation continues to neglect this important portion of inspired Scripture. But perhaps of greater consequence is the fact that the Church through the ages has therefore suffered from the lack of understanding of the unique message of this letter in its assertion of the radical supremacy of the Christian gospel over Judaic religion, and religion in general. The epistle to the Hebrews is not the only document of antiquity that is devoid of the details of origin and destination. Within the New Testament literature itself there are other examples of literature without statement of authorship or destination. John's epistles, for example, do not contain his name or any designation of his readers, but these have been reconstructed with what evidence is available (particularly in the case of First Epistle of John) to provide a meaningful historical context for interpretation. The same can be accomplished for the Epistle to the Hebrews, as we will set about to do. The task of a Biblical expositor is to consider the evidence available concerning the historical context of a document, draw a conclusion based on that evidence, and interpret the text accordingly. Biblical scholarship, with its ever-skeptical approach, has been very cowardly in drawing conclusions about the authorship of Hebrews, thus assuring that the text can have only nebulous interpretive meaning. What, then, is the evidence for authorship, destination and dating of this epistle, in order to give it specific historical context? What is the most legitimate conclusion that can be drawn based on that evidence? The primary objections to Pauline authorship have traditionally been explained as: (1) the absence of Paul's name in the epistle, (2) the apparent second-hand knowledge referred to in 2:3, and (3) the style, grammar and vocabulary of the epistle which seems to differ from other Pauline writings. The absence of Paul's name or signature was explained as early as 200 A.D. in the Hypotypos of Clement of Alexandria (c. 155-215). Though that eight volume outline of Christian thought has not been preserved, a portion of that document was quoted by Eusebius in his Ecclesiastical History:

The reason for the absence of Paul's name is hereby explained early in church history as a sensitivity of the "Apostle to the Gentiles" in writing to Hebrew peoples, who were his kinsmen. The absence of his name does not exclude Paul from authorship anymore than the absence of John's name excludes his authorship of the epistles attributed to him. The contested statement in Hebrews 2:3, "After it (the word of salvation) was at first spoken through the Lord, it was confirmed to us by those who heard," seems to evidence a second-hand knowledge of the gospel, and Paul certainly argues vehemently for the right of apostleship through a first-hand knowledge of Jesus Christ in Galatians 1:112:10. But the words can just as accurately be interpreted by explaining that Paul was admitting that he was not one of the original twelve disciples who traveled with the historical Jesus, and therefore was not privileged to directly hear the words that Jesus spoke in that context. This does not in any way diminish his apostleship that he argued for in Galatians, such argument for his apostleship to the Gentiles obviously muted in this correspondence to Jewish Christians. The argument of differing style, grammar and vocabulary is not all that conclusive either, especially since this epistle was being written to any entirely different audience and with an entirely different purpose than any of Paul's other epistles. Many of the vocabulary differences, where Paul employs words not used in other writings (hapax logomena), are in the context of his contrasting Jesus with Jewish history and theology, of which he was obviously quite knowledgeable and would not have been so apt to use in writing to Gentile congregations. The stylistic differences of the Greek text were explained by Clement of Alexandria (see above) as due to Luke's translation from Hebrew to Greek. Having considered the objections to Pauline authorship, it is incumbent upon us to now present the evidence that exists that points to Paul as the most likely author of this letter. The papyrus fragment identified as P46 is the oldest extant manuscript of the Pauline epistles. This Greek manuscript from Alexandria in Egypt is dated around 200 A.D., and there are no earlier available manuscripts of Paul's epistles. By acceptable criteria of textual criticism, the oldest manuscripts, i.e. those closest to the date of the original writing, must be given greatest import or weight in textual considerations. Since P46, the earliest manuscript containing the Pauline corpus of literature, includes the epistle to the Hebrews immediately following Paul's epistle to the Romans and attributes authorship of the epistle to the Hebrews to Paul, this ascription must be granted a predominating weight of evidence in the critical consideration of authorship. We have already noted that the eight volume Hypotypos of Clement of Alexandria, written c. 200 AD, clearly indicated that Paul was the author of the Epistle to the Hebrews, giving explanation of the absence of his name in the epistle and explanation of the variation in grammatical style of the Greek text (see quotation from Eusebius above). Origen (185-253), in his Commentary on the Gospel of John, wrote that "the Apostle Paul says in the Epistle to the Hebrews: 'At the end of the days He spoke to us in His Son' (Heb. 1:2)".2 Origen clearly attributes Pauline authorship to the epistle to the Hebrews, from which he quotes. The early Alexandrian scholars of the Eastern Church consistently regarded Paul as the author of this epistle. The scholars of the Western Church in Rome were more skeptical of Pauline authorship until Jerome (c. 340-420) and Augustine (396-430) supported the thesis of Paul's authorship. From the Sixth Synod of Carthage (419) until modern times the Roman Catholic Church affirmed Pauline authorship of the epistle of the Hebrews. The Protestant Reformers, on the other hand, revived the questioning of Paul's authorship, with Martin Luther the first to propose Apollos as the author and John Calvin speculating that Clement of Rome or Luke may have been the author. Scholastic speculations of authorship of this epistle have abounded since the Reformation, often with arrogant unwillingness to accept early tradition or to counter prevailing skepticism of scholarship. As additional evidence it should be noted that the author mentions Timothy (13:23), who was Paul's closest colleague in ministry, mentioned often in other Pauline epistles (Rom. 16:21; II Cor. 1:1; Phil. 1:1; 2;19; Col. 1:1; I Thess. 1:1; 3:2,6; Philemon 1:1). The author appears to have previously visited the group of people to whom he was writing, and hoped to revisit them (13:19,23), consistent with the fact that Paul had visited the church in Jerusalem on several occasions (Acts 21:11-31; Rom. 15:25; Gal. 1:18). The mention of the "saints of Italy" (13:24) would be consistent with Paul's imprisonment in Rome, and his desire to send greetings on behalf of the Italian Christians to the Jewish-Christian recipients of this letter. The evidence is certainly not sufficient to dismiss or deny Paul as the most likely author of this epistle to the Hebrews. In fact, we must be honest enough to admit that the preponderance of the evidence leads to Pauline authorship. All other proposed authors of this epistle (Silas, Philip, Mark, Priscilla, etc.) are merely speculative assignments, "shots in the dark" to suggest another name other than Paul. The name of Apollos was not even suggested until the 16th century by Martin Luther. There is no way to compare the literary criteria of grammar, vocabulary and style with other writings of these speculatively proposed authors for many of them have no other literature to compare with. What a convenient way to preclude Pauline authorship and preempt having to deal with the grammatical issues by assigning authorship to unpublished persons. Though one must "swim against the tide" of several centuries of skeptical academic scholarship in the textual criticism of Protestant Biblical studies, the evidence is quite sufficient to assert that the Apostle Paul was the most likely author of this epistle to the Hebrews. The text does not indicate who the first readers were, again leaving us with an anonymity of original recipients. So, what internal and external evidence can be presented to make an assignment of destination? Based upon the abundance of references to Jewish religion and the old covenant, particularly the Levitical priesthood and temple practices, this document has been referred to as "the epistle to the Hebrews," at least since the latter part of the second century AD. It is reasonable to assume that the original readers were Christians from a Jewish background, even though the quotations from the Old Testament seem to be from the Greek translation of the Septuagint (LXX), which would be consistent with Paul's bilingual knowledge of the Old Testament and his frequent utilization of the LXX among Gentiles. It appears that the author was addressing a particular community of Christians with whom he was personally acquainted. He was aware of their having endured persecution (10:32,33; 12:4), as well as their present situation (5:12; 6:9; 13:17), and intended to revisit them (13:19,23). The author and the readers were mutually acquainted with Timothy (13:23). The mention of "Italy" (13:24) in the closing comments of the epistle has caused some to conclude that the recipients were Jewish Christians residing in Rome, who were being greeted by fellow Italians living in the location from whence this epistle was written. That same reference can be interpreted to mean that the location of origination was Italy, however, and that the author is sending greetings to the readers from the Italian Christians where he is located. Although other destinations such as Alexandria, Caeserea, Ephesus, Corinth, and Antioch have been suggested, the most likely location of the residence of the original readers is Jerusalem. Who else would have had such attachment to Jewish history and theology, such close ties with Temple worship and its sacrifices, such pressure to relapse to Judaic religion, than the Hebrew saints in Jerusalem? Consider also that in subsequent Christian history no church claimed that this letter had been written to them, a practice of all the other churches who sought to make a "claim to fame" as the recipients of an apostolic letter from Paul. The church at Rome did not claim this letter. The churches at Alexandria, Ephesus, Corinth or Antioch did not claim this letter. No church claimed to be the recipients of this letter in the history of the early church. The explanation for this phenomenon is simple: within a few years after this epistle was written the church at Jerusalem ceased to exist. Jerusalem was destroyed in 70 A.D. Palestine was devastated and its inhabitants decimated. There was no church in Jerusalem to lay claim to being the recipients of this epistle after 70 A.D. This serves as an important historical evidence to the Jerusalem church having been the likely recipients of this letter. It is most reasonable to assume that Paul was imprisoned in Rome in the mid-60s of the first century (as we know from Luke's account in the Acts of the Apostles 28:16-31), and he had a good social and spiritual perspective of what was going on in the Roman persecutions of Christians under Emperor Nero (who died in 68 A.D.), as well as the Roman attitudes toward the Palestinian Jews. He also knew the attitudes of the Palestinian Jews with their intense nationalist patriotism, their religious absolutism, their racist superiority, and he could foresee that a violent war was about to erupt in Palestine between the Romans and the Jews. The Christian Jews in Palestine had lost their leaders (13:7), and Paul, though he knew he was the Apostle to the Gentiles (Acts 9:15; Rom. 1:5; Gal. 1:16; 2:7), never lost his heart for his Jewish kinsmen (Rom. 9:3). It is likely that he decided to write this letter to encourage (13:22) the Jewish Christians in Jerusalem to be confident in their endurance (10:35,36) by emphasizing the superiority of Jesus over all religion. The Palestinian Christians were being pressured to revert to Judaism, to join the patriotic cause of militaristic defense against the Roman empire. Christianity did not seem to be going anywhere except among the Gentiles, and even then Paul was on death-row in Rome. Some of the Christians were not even assembling together anymore (10:25), were becoming casual about sin (10:26; 12:10-16), and were in danger of apostasizing (6:4-6; 10:26-31). Paul writes to encourage these Palestinian Christians not to take the easy way out and revert to religion again, in particular Judaism, with its religious practices and nationalistic patriotism. He explained that the old covenant of God's working with and through the Jews, was obsolete and would soon disappear in destruction (8:13) as it soon did in 70 A.D. The old covenant was only intended to pre-figure and set-up the new covenant of all that God intended to do in His Son, Jesus Christ. Jesus is the fulfillment of all the old covenant pictures and types, the fulfillment of all God's intents and promises (II Cor. 1:20) for His people. "Don't go back to religion," Paul is saying. "Go outside the camp" (13:13), repudiate Judaism, perhaps even consider leaving Jerusalem and Palestine (as many of them did, and survived the Roman slaughter of 70 A.D.). To reject Christ and go back to Judaic religion (any religion) is fatal and final, Paul indicates (10:29-31). Paul was telling the Palestinian Christians that there was a polarity of either/or, either Christ or Judaism, but you cannot have both. Like oil and water, Christian and religion do not mix! J. Bramby explains that

If, as the evidence suggests, Paul wrote this epistle to the church in Jerusalem which was undergoing persecution (not only by the Romans, but even more by the Palestinian Jews - cf. 10:32-36), then this epistle was one of the last, if not the last, that Paul wrote. Why is this important? Because if the epistle to the Galatians was the first of Paul's extant epistles, and the epistle to the Hebrews was the last, then we can observe the total consistency of Paul's thinking throughout his ministry. Galatians and Hebrews are two of the clearest New Testament epistles exposing the radical uniqueness of Christianity as set against the old covenant and Judaic religion. All of Paul's other writings must then be interpreted in the context of Galatians and Hebrews, as they form the alpha and omega of the Pauline corpus, serving as the "bookends" of Pauline theology. There is also no direct indication of the date of writing in the text of this epistle. Most scholars have concluded that it was written prior to the fall of Jerusalem in 70 AD since there is no reference to that catastrophic historical event, and one would certainly expect such had it been written to Christian readers of Jewish background after that event. The writer's repeated references to Jewish rituals using present tense verbs (7:8; 9:6-13; 13:10,11) also seems to indicate a date when such practices were still being performed in the temple at Jerusalem prior to its destruction. The only other referent point for dating this document is that Clement of Rome was apparently acquainted with this epistle by approximately 95 A.D. It is quite likely that Emperor Nero's "urban renewal project" had just occurred in Rome, when in 64 AD Nero had apparently arranged to burn a large section of Rome in order to clear the way for his building campaign which would memorialize him in its lasting grandeur. "Nero fiddled while Rome burned" was the scuttlebutt that prevailed at the time, and the phrase remains as a lasting indictment to that imperial crime. The Christians, regarded as but a sect of the Jews at the time, became Nero's scapegoat of blame for setting the fire, igniting an incendiary wave of suspicion and persecution against the Christians, as well as the Jews. Paul, under house arrest in Rome, might well have observed the glow of the flames and smelled the smoke from the fire. Hearing that the Christians had been blamed for setting the fire, Paul may have "seen the handwriting on the wall", so to speak, and realized that the days ahead would be difficult times for Christians and Jews. Paul was also well aware of the growing sentiment of resentment against Rome in Palestine, with the feverish swell of nationalistic patriotism being incited by the Zealot party within Judaism, advocating their alleged God-given right as the "chosen people" of God to operate as a sovereign nation in the line of David within the Palestinian land that they regarded as their "promised land." But Paul may have had a much better perspective of the might and power of the Roman army than the Palestinian peoples had in their blind fervor for self-rule. He may have had grave concerns of the outcome if the Roman military were to move into Palestine to put down an insurrection of revolt against Rome by the Jewish nationalists. Aware of attitudes both in Rome and Palestine, Paul may have decided that this was a timely opportunity to encourage his Christian brothers in Jerusalem by writing an epistle to the Church there, encouraging them to remain faithful to Jesus Christ and not to succumb to the political and religious influences that were being brought to bear upon them at that time. The best conclusion, based on the evidence, seems to indicate that this letter was written by Paul from Rome to the Hebrew Christians in Jerusalem in the middle 60s of the first century, perhaps in 64 or 65 AD just prior to Paul's likely execution at the hands of the Romans. Be forewarned that the epistle to the Hebrews contains what is perhaps the most radical message in the New Testament. It may upset the applecart of your religious understanding. No other book in the New Testament so categorically asserts that God's arrangement with men in the Old Testament is no longer valid, making that point by declaring that Jesus is better than every feature of the old covenant. To drive the point home the readers are warned that if they revert to the Judaic religious practices of their past, having participated in the new covenant realities of Jesus Christ, they will forfeit all opportunity to participate in the eternal realities of Jesus Christ again. With at least eighty-six direct references to the Old Testament within this letter, and with constant attention drawn to the Jewish people and their religion, it is important to consider the correlation of this document to the Old Testament. Some have indicated that a thorough understanding of the Old Testament is essential to understanding the epistle to the Hebrews. Though it is true that an understanding of the historical background and ritualistic practices of the old covenant and the Hebrew peoples provides a valuable context for interpreting this document, it is perhaps even more important to realize that a thorough understanding of the Epistle to the Hebrews is essential to a proper understanding of the Old Testament from a Christian perspective. If the "Old Testament is the New Testament concealed, and the New Testament is the Old Testament revealed," as has often been explained as the basis for Christian hermeneutics, then the revealing of the gospel, especially in the book of Hebrews, should serve as the starting-point to consider how the gospel was concealed in the clues of the prefiguring of the Old Testament. The failure to interpret the Old Testament from this perspective has led to much confusion and misemphasis in Christian teaching, allowing the Old Testament to serve as the priority literature even in the lives of new covenant Christians. When this happens Christianity is perverted into religious forms of Christianized Judaism, which is the very thing that this epistle warns against and condemns. The Epistle to the Hebrews is the best antidote to such religious perversion, serving as the necessary commentary on the Old Testament, and interpreting the history, worship and prophecy of the Old Testament as it points in its entirety to Jesus Christ. Clyde F. Whitehead explains that

J. Barmby, writing in the Pulpit Commentary, comments that

The Epistle to the Hebrews is pivotal to understanding the old covenant literature of the Old Testament. It is equally as pivotal to understanding all of the rest of the new covenant literature of the New Testament. This epistle might well have been placed as the first book in the New Testament canon arrangement, providing the bridge that explains the preliminary purpose of God in the old covenant and the superlative fulfillment of God's purpose in the new covenant, i.e. in Jesus Christ. Over and over the author of the Epistle to the Hebrews uses the word "better" to describe the spiritual reality afforded in Jesus Christ. Christians have a "better hope" (7:19) within a "better covenant" (7:22; 8:6) with "better promises" (8:6). "God has provided something better for us" (11:40) by the "better sacrifice" (9:23) of Jesus Christ, that we might enjoy the "better possession" (10:34). This theme provides the basis of our entitling this study, "Jesus Better Than Religion." R.B. Yerby writes,

Those who fail to understand the better reality of the new covenant in Jesus Christ as plainly expounded in the epistle to the Hebrews, tend to have a false hope for a reversionary return to the physical and external rituals of old covenant Jewish religion. This has become a popular theological interpretation in Western Christendom. Yerby responds to such by noting that,

Proper understanding of the Epistle to the Hebrews will reveal the logical absurdity of any expectations that God is going to renew the Jewish religion, re-establish a physical kingdom, reinstitute the Jewish priesthood, reinstate the animal sacrifices, rebuild the Jewish temple, or restore the physical land. Such expectations are the very backward reversions to religion that this epistle warns against, by explaining that all such external and physical religion has been superseded in the spiritual reality of Jesus Christ. In the epistle to the Hebrews we are inculcated to "consider Jesus" (3:1; 12:3) as the spiritual reality that God has made available for all men. The ontological dynamic of the living Lord Jesus by His Spirit is the essence of Christianity. This Christocentric emphasis is at the heart of all of the inspired literature of the New Testament, and is certainly the focal point of this letter. Jesus is better than all religion because He is personal. The Personal, Living God sent His Son as the God-man to personally redeem and restore mankind. Only by the dynamic Person and Life of Jesus Christ can man be restored to function as God intended in a personal faith/love relationship with God. To revert to religion is to settle for impersonal things, events, places and practices which can never satisfy. Jesus is better than all religion because He is the singular, exclusive, ultimate and final revelation of God to man. He is the sum of all spiritual things (cf. Eph. 1:10), allowing for no religious syncretism or admixture. Though religion regards such an assertion as "the scandal of singularity and exclusivism," Jesus is the only "mediator between God and man" (I Tim. 2:5). "No man comes unto the Father, but by Me" (Jn. 14:6). "There is no other name under heaven whereby a man must be saved" (Acts 4:12). Jesus is better than all religion because of the completeness and permanency of His finished work (Jn. 19:30). Whereas religion is limited, temporary and repetitive, the life of Jesus is eternal and forever. As a "priest forever" (5:6), Jesus is "eternal salvation" (5:9) within the "eternal covenant" (13:20). Jesus is better than all religion because He is the provision and sufficiency for practical experiential behavior that glorifies God. The impracticality of religious belief-systems, moralities, and rituals are most unsatisfying, but "through Jesus Christ we are equipped in every good thing to do God's will" (13:20). The writer of the epistle to the Hebrews exalts Jesus Christ as the essence of the Christian gospel. Christianity is not religion; Christianity is Christ! Jesus is better than all religion. 1 Eusebius,

Ecclesiastical History. VI,14,2. A Select Library of

Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers

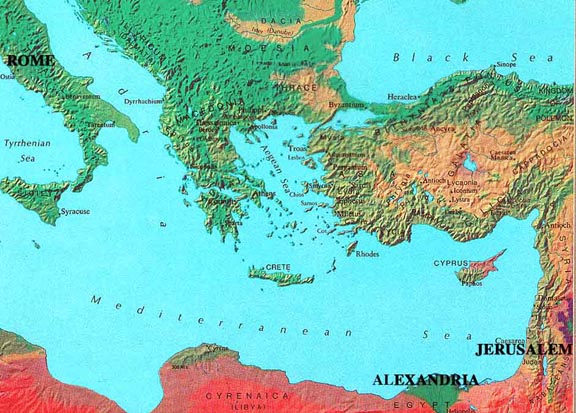

Map of Mediterranean Region with primary locations pertaining to the Epistle to the Hebrews  |